I’ve been seeing a lot of articles about alternatives to traditional bonds and their ultra-low interest rates. The 5-year US Treasury rate is closer to zero than even 1%, an all-time low even considering the past decade (source):

Warnings about the dangers of chasing yield are for good reason. We need to be very skeptical. In a relatively quiet corner of the annuity world, you can get a “guaranteed” rate of 3% and above. This chart from Blueprint Income (via indexfundfan) shows the gap between the top 5-year MYGA rate and a 5-year Treasury, with a rate difference of 3.20% as of September 2020. The gap is slightly smaller as of this writing in late October 2020.

This is a huge gap if the level of safety is comparable. But is it? I actually bought a $10,000 MYGA contract back in 2015 as an educational investment, but never really wrote about it because it is relatively complex and I wasn’t sure it was worth the additional effort when the interest rate gap was much smaller. But given the growing gap, I think a DIY investor should consider at least learn about it as a potential part of their toolkit in 2020.

What are MYGAs? A “MYGA” is a form of fixed deferred annuity that offers a multi-year rate guarantee. For example, they may promise an annual interest rate of 3% for 5 years. This is similar to the rate guarantee from a bank certificate of deposit. However, there are several important differences between a MYGA and an FDIC-insured bank CD.

Annuities are bad though, right? Not all annuities are the same. I like the slogan of Stan “the Annuity Man” Haithcock: “Will do. Not Might do.” In others words, look for concrete promises with no wiggle room, not a “theoretical illustration based on historical returns”. A deferred annuity should state a fixed interest rate (ex. 3% for 5 years). A single-premium immediate annuity should promise you a fixed monthly income for the rest of your life (ex. $1,233 per month). Hard numbers, not a confusing formula based on the stock market (always quietly stripped of dividends).

Annuities also have a bad reputation because many have high commissions to encourage their sale. Often, the worse the annuity, the higher their commissions. However, MYGAs have relatively low commissions, often between 1% and 2.5% upfront (one-time) for the most competitively priced ones. On the flip side, many financial advisors won’t recommend an annuity because they don’t get paid an “assets under management” fee on them (which might be 1% every year, forever!).

Early withdrawal penalties. However, all annuities do have some complications to understand. Once you buy an annuity, you must keep it in an annuity and not withdraw until age 59.5, otherwise you will be subject to a 10% penalty on top of the taxes owed. It is a long-term commitment of funds, similar to an IRA contribution. However, after a 5-year MYGA contract expires, you can simply roll it over into another 5-year MYGA with the same or different provider. This is what I plan to do until I am past age 59.5. If you buy an MYGA with after-tax money, your interest gets to compound tax-deferred until you make a withdrawal. This can be helpful if you have already maxed out your IRA and 401k limits. (You could also convert to a single-premium immediate annuity with a guaranteed income stream.) Upon withdrawal, you will owe income tax on the gains (not principal).

Additional liquidity concerns. An early withdrawal before the end of your fixed term also will be subject to another large penalty, including a market-value adjustment and surrender charges. Some MYGA contracts allow small withdrawals, like 5% or 10% of the purchase amount per year. In general, this is not a good place for “emergency funds”.

“Guarantee”. This word is used frequently with insurance and annuity products. “Guaranteed income.” This only means it is “guaranteed” subject the claims-paying ability of the issuing insurance company. What happens if the insurance company can’t pay? This falls back onto the coverage limits of your state’s Life & Health Guaranty Association. From NOLHGA.com:

State guaranty associations provide coverage (up to the limits spelled out by state law) for resident policyholders of insurers licensed to do business in their state. NOLHGA assists its member associations in quickly and cost-effectively providing coverage to policyholders in the event of a multi-state life or health insurer insolvency.

When an insurer licensed in multiple states is declared insolvent, NOLHGA, on behalf of affected member state guaranty associations, assembles a task force of guaranty association officials. This task force analyzes the company’s commitments to policyholders; ensures that covered claims are paid; and, where appropriate, arranges for covered policies to be transferred to a healthy insurer.

The task force may also support the efforts of the receiver to dispose of the company’s assets in a way that maximizes their value. When there is a shortfall of estate assets needed to pay the claims of covered policyholders, guaranty associations assess the licensed insurers in their states a proportional share of the funds needed.

While the coverage limits vary from state to state, virtually all states offer at least $250,000 in coverage for the present value of an annuity contract. (Connecticut, New York, and Washington offer $500,000 in coverage. In California, the limit is only 80% not to exceed $250,000.) Look up your specific state’s limits here and here. Here is a reference chart (click to enlarge, source):

Unfortunately, this is not the same as being backed by the federal government, as with FDIC-insurance. It’s not even a state government backing, as only the member insurance companies have agreed to cover each other in cases of insolvency up to the policy limits. The guaranty system has not resulted in a loss to consumers within the limits since their inception in the 1980s, meaning it worked through the 2000 and 2008 market crashes. In order to be a licensed member of that association, you need to maintain a certain level of financial stability and under regular audits. Each individual insurer also rated by various agencies like AM Best, Moody’s, or Standard & Poors. In the end, there remains a possibility that an extremely large event could happen that would result in the inability of the stronger companies to help all the weaker ones. I recommend reading this paper about how the state guaranty system works in a failure.

It’s hard to put a number on the possibility of a partial loss even with this state guaranty system, but I’d definitely rather be covered with it than without. In this older 2013 post, I wrote about MYGAs and how to structure your accounts to stay within your state’s specific coverage limits.

Higher-rated insurers typically pay lower interest rates, and lower-rated insurers typically pay higher interest rates. There are different strategies on how to navigate this system. One is to decide on the lowest safety rating that you will accept, and then find the highest interest rate available with that minimum rating. Another is to simply trust in the state guaranty system and treat all the insurers as equal as long as you remain below the state-specific coverage limits. In that case, you simply buy the highest interest rate available from a licensed insurer.

If you are trying to understand what the ratings mean, first refer to the AM Best Ratings Guide [PDF], which states that “A Best’s Financial Strength Rating (FSR) is an opinion of an insurer’s ability to meet its obligations to policyholders.” followed by:

- A++, A+. Assigned to insurance companies that have, in our opinion, a superior ability to meet their ongoing insurance obligations.

- A, A-. Assigned to insurance companies that have, in our opinion, an excellent ability to meet their ongoing insurance obligations.

- B++, B+. Assigned to insurance companies that have, in our opinion, a good ability to meet their ongoing insurance obligations.

I don’t know about you, but I would rate that as “Super Vague++”. Marginally more helpful is the fact that in the past, AM Best categorized the following as “Secure” : A++, A+ A, A- B++, B+. Anything below that fell to “Vulnerable”.

Here is another chart from AM Best that lists cumulative impairments over different time periods (via the Bogleheads forum):

It is important to note that an impairment does not necessarily mean that the insurer could not pay out the interest. It simply means that some sort of negative action was taken by a state regulatory agency. The insurer may be put under “administrative supervision” and may later exit while never missing any payments. Or, the insurer may be taken into conservatorship and the assets sold/transferred to a solvent insurer, again never missing any payments.

Again, I would spread out my MYGA contracts across multiple insurers and make sure the final size is well below your state’s contractual limits. For example, if the limit is $100k you put exactly $100k in a single contract at 3% interest for 5 years, at the end you’ll have over $115,000 and thus have $15k of your funds exposed.

Where do I buy a MYGA? I am not a insurance professional and I’ve probably missed some details. But I also get no commission if you buy one of these things. As a consumer, you should know the MYGA commission is baked inside and the upfront price is the same no matter who you buy it from. Back when I bought my MYGA in 2015, I did my own research and chose to buy from “Stan the Annuity Man”. You can find the MYGA section of his site here with rates for your specific state. I had a positive experience and would recommend him, especially if you prefer to have a reliable person-to-person relationship with good communication. I am not affiliated with Stan, other than being a satisfied customer. In 2020, there are more “fintech” options including the Blueprint Income marketplace. Both of those websites are have an educational section with more information about MYGAs in general.

At the end of your MYGA contract, you will have short (30-day?) window where you can make a 1035 transfer to another annuity provider (or renew with the same provider at prevailing rate). I was given plenty of heads up by The Annuity Man team. Again, the price should be same no matter where you buy it, so I would pick the place you think you’ll get better customer service. It might even be a local broker.

Bottom line. This is a brief introduction to a unique annuity product called the MYGA (multi-year guaranteed annuity) that offers a fixed, tax-deferred yield that may be significantly higher than that of other investment-grade bonds like US Treasuries. There are many important factors to understand, including insurer stability ratings, state guaranty limits, liquidity rules, and surrender charges. I’ve probably overlooked something as well. MYGAs are best if you are a motivated DIY investor looking for higher-yielding fixed-income investments and have maxed out your other tax-deferred options like IRAs and 401(k) plans.

Savings I Bonds are a unique, low-risk investment backed by the US Treasury that pay out a variable interest rate linked to inflation. With a holding period from 12 months to 30 years, you could own them as an alternative to bank certificates of deposit (they are liquid after 12 months) or bonds in your portfolio.

Savings I Bonds are a unique, low-risk investment backed by the US Treasury that pay out a variable interest rate linked to inflation. With a holding period from 12 months to 30 years, you could own them as an alternative to bank certificates of deposit (they are liquid after 12 months) or bonds in your portfolio.  After reading the

After reading the

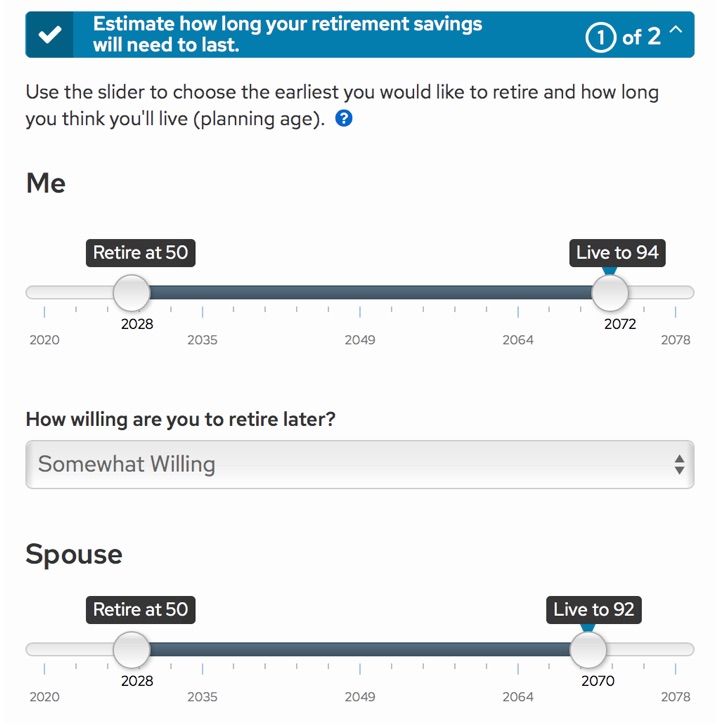

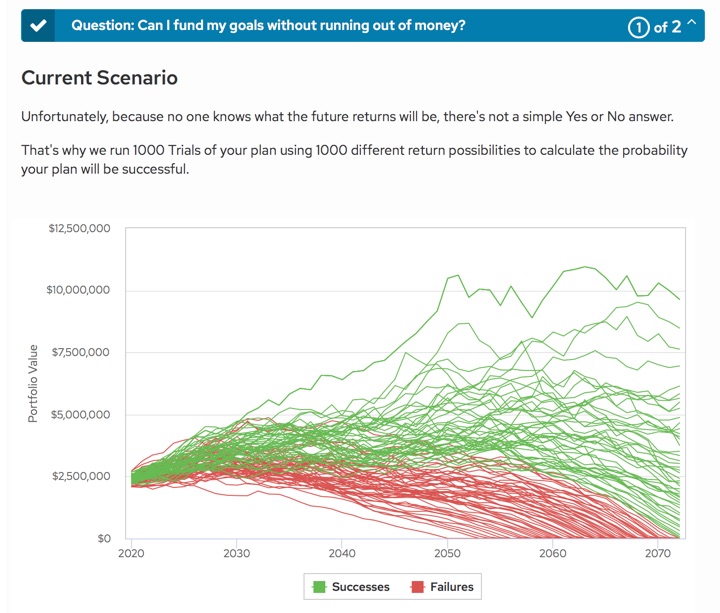

Schwab has rolled out a new digital financial planning tool called

Schwab has rolled out a new digital financial planning tool called

The third book in the “Investing for Adults” series by William Bernstein is

The third book in the “Investing for Adults” series by William Bernstein is

When to start claiming Social Security to maximize your potential benefit can be a complicated question, especially for couples. There are multiple paid services that will run the numbers for you, including

When to start claiming Social Security to maximize your potential benefit can be a complicated question, especially for couples. There are multiple paid services that will run the numbers for you, including

I started looking into financial independence because I simply couldn’t imagine doing what I was doing every weekday at that time for another 30 or 40 years. Some people know exactly what they want to spend their life doing, and it also pays the bills and then some. I was always envious of those folks. Strangely, I never really felt that making more money was the final answer. I saved diligently in order to quit my job and go back to school and explore alternate paths.

I started looking into financial independence because I simply couldn’t imagine doing what I was doing every weekday at that time for another 30 or 40 years. Some people know exactly what they want to spend their life doing, and it also pays the bills and then some. I was always envious of those folks. Strangely, I never really felt that making more money was the final answer. I saved diligently in order to quit my job and go back to school and explore alternate paths.

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025 Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps

Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025

Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025 Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring

Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers

Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money

Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill

How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)

Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)