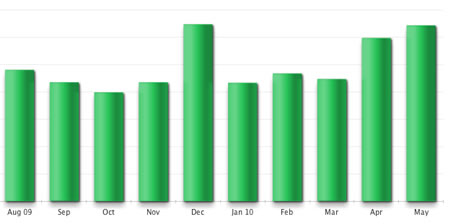

Time for another net worth update… last one was back in April.

Credit Card Debt

I used to take money from credit cards at 0% APR and place it into online savings accounts, bank CDs, or savings bonds that earned 4-5% interest (much less recently), keeping the difference as profit while taking minimal risk. (Minimal in regards that the risk was under my control.) However, given the current lack of great no fee 0% APR balance transfer offers, I am currently not playing this “game”.

Most credit cards don’t require you to pay the charges built up during a monthly cycle until after a grace period of about 14 days. This theoretically provides enough time for you to receive your statement in the mail and send back a check. As this is simply a real-time snapshot of my finances, my credit card debt consists of just these charges.

Retirement and Brokerage accounts

We recently converted our Traditional IRA balances to Roth IRAs, as the income restrictions were lifted this year. The choice to convert was rather simple for us, as we had non-deductible contributions that will now be able to be withdrawn tax-free. (We still owe taxes on very modest gains.)

Our total retirement portfolio is now $289,277 or on an estimated after-tax basis, $249,976. At a theoretical 4% withdrawal rate, this would provide $833 per month in after-tax retirement income, which brings me to 33% of my long-term goal of generating $2,500 per month.

Cash Savings and Emergency Funds

We are now a bit below a year’s worth of expenses (conservatively estimated at $60,000) in our emergency fund. This is after withholding some money for paying taxes on the Roth IRA conversion above, and also for undisclosed, one-time recent expenses. It’d be fun to say that we picked up a convertible or something, but the reality is much less exciting. 😛

Our cash savings is mostly kept in a combination of a rewards checking account (with debit card usage requirements), a SmartyPig account at 2.15% APY currently, or in a 5-year CD from Ally Bank, which despite the long term still provides a very competitive yield even if you withdraw early before the 5 years is up. (See here for more details.)

Home Value

I am still not using any internet home valuation tools to track home value. After using them for a year and finding them unreliable, I am back to maintaining a conservative estimate and focusing on mortgage payoff. If we get some positive cashflow after retirement savings, I do want to pay it down faster.

We are all leading busy lives, and it’s all to easy to “miss the woods for the trees”. What if we prioritized by taking a step back and simply asked ourselves – what is our most important asset? Are we adequately protecting that asset?

We are all leading busy lives, and it’s all to easy to “miss the woods for the trees”. What if we prioritized by taking a step back and simply asked ourselves – what is our most important asset? Are we adequately protecting that asset?

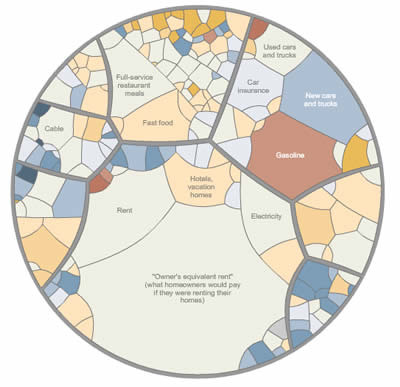

The NY Times has a new series called the

The NY Times has a new series called the  The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025

The Best Credit Card Bonus Offers – 2025 Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps

Big List of Free Stocks from Brokerage Apps Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025

Best Interest Rates on Cash - 2025 Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring

Free Credit Scores x 3 + Free Credit Monitoring Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers

Best No Fee 0% APR Balance Transfer Offers Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money

Little-Known Cellular Data Plans That Can Save Big Money How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill

How To Haggle Your Cable or Direct TV Bill Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)

Big List of Free Consumer Data Reports (Credit, Rent, Work)